Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Empyema Thoracis in Children – Tailored Surgical Therapy for Late Referrals: A Single Unit Experience – Study in Suburban Mumbai Volume 4 - Issue 1

Patankar Jahoorahmad Z1*, Susan Fernandes2, Allan Pereira3, Ankit Desai4, Shiva Prasad Hirugade5, Dattatray B. Bhusare6, Hemant Lahoti7 and Manjusha Sailukar8

- *1Consultant Pediatrician & Newborn Surgeon, Pediatric Urology and Laparoscopy, The Children’s Hospital Mumbai, India

- 2Consultant Paediatrician & Neonatologist (Fellowship in Neonatal Intensive care), The Children’s Hospital Mumbai, India

- 3Consultant Paediatrician, The Children’s Hospital Mumbai, India

- 4Senior Paediatric Anaesthesist, Children’s Anaesthesia Services, Mumbai, India

- 5Consultant Paediatric Surgeon & Associate Professor, R.C.S.M. Government Medical College, Kolhapur, India

- 6Consultant Paediatric Surgeon & Professor. Dept of Surgery, Head of Paediatric Surgery & Head of Dept of Emergency Medicine, MGM Institute of Health Sciences, Mumbai, India

- 7Consultant Paediatric Surgeon & Associate Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, D. Y. Patil Hospital, Mumbai, India

- 8Consultant Paediatric Surgeon & Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, KJ Somaiya Medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Mumbai, India

Received: December 21, 2022 Published: January 05, 2023

Corresponding author: Patankar Jahoorahmad Z, Consultant Pediatrician & Newborn Surgeon, Pediatric Urology and Laparoscopy, The Children’s Hospital Mumbai, India

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2023.04.000177

Abstract

Overview

a) Empyema Thoracic (ET) is a frequently encountered clinical problem and is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Diagnosis may be difficult; delay in treatment contributes to morbidity, complications, and mortality [2].

b) The ideal management strategy for ET has not been elucidated due to a paucity of properly conducted randomized controlled trails.

Objectives: Despite the reported value of institution of early drainage for ET, many children continue to be “referred late” in the disease process – STAGE II or III3 and beyond one to three weeks after diagnosis of ET. The author wishes to determine the optimal management for this group of children.

Methods: Over a three-year period – A total of 142 children with ET were referred to a single Paediatric surgeon (first author). Sixty (42%) were diagnosed as late-presenting ET (STAGE II or III) and were referred late - one to three weeks after diagnosis of ET had been established. Patients were grouped as follows:

Group 1: Managed with Intercostal Drainage (ICD) alone (n=82).

Group 2: Managed by Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) alone (n=30).

Group 3: VATS converted to Open Decortication (n=14).

Group 4: Early Thoracotomy & Decortication (n=16).

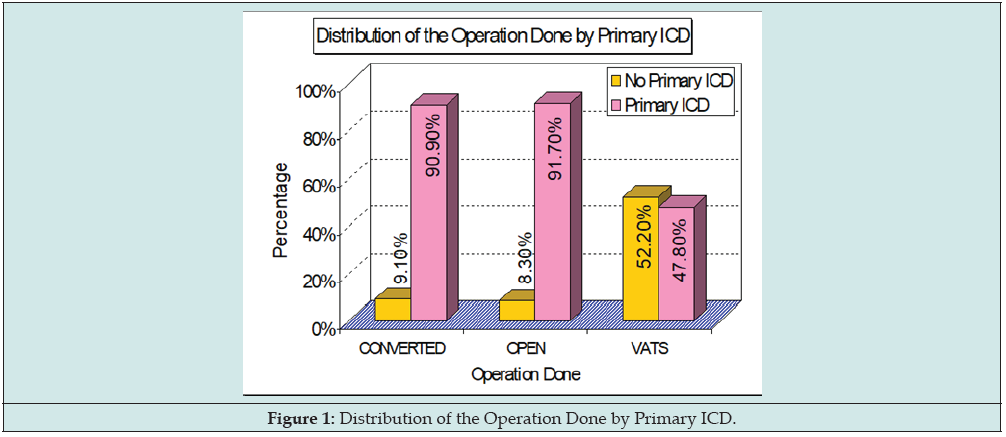

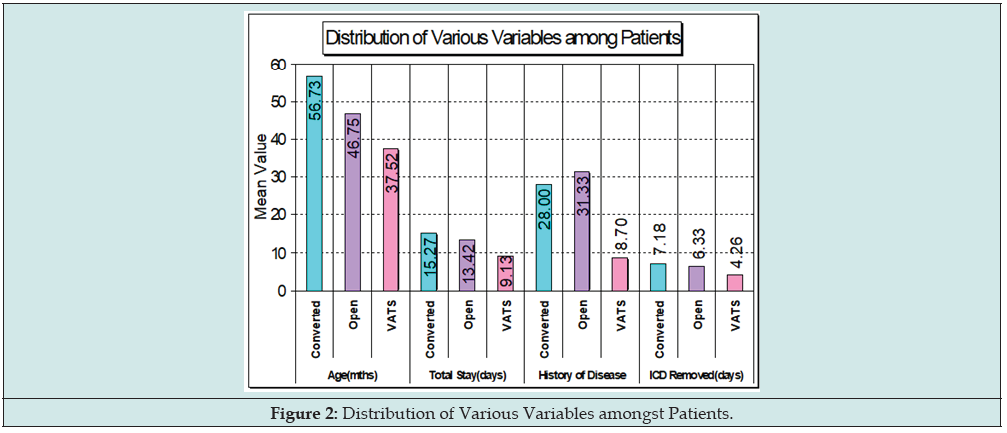

Results: 82 (58%) were early referrals (within one week of diagnosis of ET) and could be successfully managed with ICD alone (Group 1). 60 (42%) of late-presenting ET required some form of surgical intervention (Groups 2, 3 & 4). Primary ICD could be avoided in half of VATS i.e., Group 2 as compared to Groups 3 & 4 (Figure 1). There were no significant differences with respect to age, gender, pleural cultures, or fluid analysis amongst any of the groups. Figure 2 gives the distribution of various variables amongst patients. Treatment using ICD alone (Group 1) although successful in 58% of patients was associated with prolonged length of stay (LOS) when compared to Early Thoracotomy & Decortication (Group 4; 14 days vs 13.42 days). For Groups 2 and 4 rapid clinical improvement and early discharge (9.13 to 13.42 days) was seen after surgery. For all surgery groups, VATS alone i.e., Group 2 (n=30) had a longer post-operative febrile period (4.5 vs 2.5 days), but a shorter total LOS (9.13 vs 13.42 days) when compared with Early Thoracotomy & Decortication i.e., Group 4 (n=16). Group 3 patients VATS Converted to Open Decortication (n=14) were noted to have the longest hospital stay (15.27 days). There was no mortality in our series.

Conclusion: Drainage of ET will be required at some stage, and an early surgical consultation is desirable in a child with an ET.

Keywords: Empyema thoracic; children; late disease process; surgical therapy

Overview

a) Empyema Thoracic (ET) is a frequently encountered clinical problem and is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Diagnosis may be difficult; delay in treatment contributes to morbidity, complications, and mortality [2].

b) The ideal management strategy for ET has not been elucidated due to a paucity of properly conducted randomized controlled trails.

Objectives

Despite the reported value of institution of early drainage for ET, many children continue to be “referred late” in the disease process – STAGE II or III [3] and beyond one to three weeks after diagnosis of ET. The author wishes to determine the optimal management for this group of children.

Methods

Over a three-year period – A total of 142 children with ET were referred to a single Paediatric surgeon (first author). Sixty (42%) were diagnosed as late-presenting ET (STAGE II or III) and were referred late - one to three weeks after diagnosis of ET had been established. Patients were grouped as follows:

Group 1: Managed with Intercostal Drainage (ICD) alone (n=82).

Group 2: Managed by Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) alone (n=30).

Group 3: VATS converted to Open Decortication (n=14).

Group 4: Early Thoracotomy & Decortication (n=16).

Results

82 (58%) were early referrals (within one week of diagnosis of ET) and could be successfully managed with ICD alone (Group 1). 60 (42%) of late-presenting ET required some form of surgical intervention (Groups 2, 3 & 4). Primary ICD could be avoided in half of VATS i.e., Group 2 as compared to Groups 3 & 4 (Figure 1). There were no significant differences with respect to age, gender, pleural cultures or fluid analysis amongst any of the groups. Figure 2 gives the distribution of various variables amongst patients. Treatment using ICD alone (Group 1) although successful in 58% of patients was associated with prolonged length of stay (LOS) when compared to Early Thoracotomy & Decortication (Group 4; 14 days vs 13.42 days). For Groups 2 and 4 rapid clinical improvement and early discharge (9.13 to 13.42 days) was seen after surgery. For all surgery groups, VATS alone i.e., Group 2 (n=30) had a longer postoperative febrile period (4.5 vs 2.5 days), but a shorter total LOS (9.13 vs 13.42 days) when compared with Early Thoracotomy & Decortication i.e., Group 4 (n=16). Group 3 patients VATS Converted to Open Decortication (n=14) were noted to have the longest hospital stay (15.27 days). There was no mortality in our series.

Discussion

Empyema, an accumulation of infected fluid within the thoracic cavity, is commonly secondary to post-infectious pneumonia. It can also occur after thoracic operations, trauma, or esophageal leaks. The American Thoracic Society has described 3 stages of empyema, namely exudative, fibrinopurulent and organized, more or less based on the characteristics of the contents of the pleural cavity. Apart from the fluid, organized fibrinous deposits appear early in the disease preventing complete drainage of fluid as well as penetration of antibiotics. An inflammatory peel of variable thickness soon forms preventing complete lung expansion. This leads to a variable clinical course creating a lot of confusion about the exact method of management. The disease becomes chronic and delayed late referrals to the surgeons by the community physicians is common world over. We have also observed like others, a definite discrepancy in the treatment modality advocated by non-surgical and surgical specialists [4]. Surgeons themselves are reluctant to operate partly due to inexperience and because of the fear of “postoperative morbidity” mentioned in Paediatric literature. However, it is a condition which if approached by the correct surgical technique gives excellent results with minimal morbidity.

Clinical Presentation of Late Referrals

Often, there is a history of multiple chest tube insertions. After an initial period of response, the drainage has usually ceased with no commensurate improvement in the clinical condition of the patient [5]. Referral is usually with multiple chest radiographs, hemograms and culture reports but the most important investigation is a recent contrast enhanced computed tomographic (CECT) scan of the chest. This (CECT) and the clinical status of the child are the cornerstones for reaching the correct decision on surgical management. A chest radiograph provides only two-dimensional information. It may only show opacity occupying a certain area of the hemithorax, which may be secondary to consolidated parenchyma, pleural peel, or a lung abscess. On the other hand, the ability of CECT to show the thorax in various sections and planes helps to reveal precise information about the location, density, and volume of the fluid along with the thickness of the pleural peel and the status of the underlying lung with its degree of entrapment. Loculations may be single or multiple, may contain pus, air, or both. Sometimes, the loculated pus can occupy the entire hemithorax and masquerade as a lung cyst. Patients may present with bilateral empyema. Lung necrosis may be associated in any of the scenarios. It may be secondary to incorrect placement of the chest tube. More often it is due to the severity of the disease process and may involve a part of a lobe, the entire lobe or rarely the entire lung.

Management of Late Referrals

The management of thoracic empyema in children continues to evoke controversies from the past five decades. Treatment options include antibiotics alone or in combination with thoracentesis, [6] tube thoracostomy (chest drain), intrapleural fibrinolytics, [7,8] thoracoscopy, [9-12] and open decortication [13-18]. Reported series illustrate the striking variability in therapeutic approach in different centres but provide little evidence in establishing the ideal treatment especially in late referrals. In the absence of good clinical evidence, the choice among these options tends to be dictated by institutional traditions, personal experiences, and biases. Open decortication is an invasive procedure, leaving significant postoperative pain and a thoracotomy scar. Thoracoscopic decortication is less invasive but leaves multiple smaller scars and requires prolonged general anesthesia. There are essentially two arguments for carrying out these procedures. The first is that the organized fibrinous deposits which appear early in an empyema impede drainage from and antibiotic penetration into the pleural space, and therefore prevent the infection from resolving, hence delaying discharge. The second is that the inflammatory “peel” prevents the lung from re-expanding properly and causes long term restriction.

Goals of Surgery in Late Referrals

(1) Thorough pleural debridement (2) release of encased lung parenchyma by carefully removing the thick plural peel from the entire lung surface and making the lung expand (3) meticulous closure of all major air leaks and (4) excision of necrotic lung tissue, which may be required in nonresponsive necrotizing pneumonias, fungal pneumonias, and parenchymal abscesses. Only standard open thoracotomy can attain all the above described 4 surgical goals in comparison to thoracoscopic procedures and the mini thoracotomy described by Raffensperger. In addition, lung expansion can be easily assessed prior to closure.

Conclusion

Empyema thoracis can produce significant morbidity in children if inadequately treated. Correct evaluation of the stage of the disease, the clinical condition of the child and proper assessment of the response to conservative treatment is crucial in deciding the mode of further surgical intervention. This ranges from intercostal chest tube drainage and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to open decortication. Surgical decortication becomes mandatory in late referrals; it gives very gratifying results ameliorating the disease rapidly and is well tolerated by young patients. Drainage of ET will be required at some stage, and an early surgical consultation is desirable in a child with an ET.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Conference Presentation

Presented at EAP-2015 European Academy of Pediatrics Congress & Master Course. AT OSLO Norway. September 2015.

References

- Mangete ED, Kombo BB, Legg-Jack TE (1993) Thoracic empyema: a study of 56 patients. Arch Dis Child 69(65): 587-588.

- Schultz KD, Fan LL, Pinsky J, Ochoa L, Smith EOB, et al. (2004) The changing face of pleural effusions in children: Epidemiology and Management. Pediatrics 113(6): 1735-1740.

- American Thoracic Society (1962) Management of non-tuberculous empyema. Paediatr Respir Rev 85: 935-936.

- Chan W, Keyser-Gauvin E, Davis GM, Nguyen LT, Laberge JM (1997) Empyema thoracis in children: A 26-year review of the Montreal Children's Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg 32(6): 870-872.

- Khakoo GA, Goldstraw P, Hansell DM, Bush A (1996) Surgical treatment of parapneumonic empyema. Pediatr Pulmonol 22(6): 348-356.

- Freij BJ, Kusmiesz H, Nelson JD, McCracken Jr GH (1984) Parapneumonic effusions and empyema in hospitalised children: a retrospective review of 227 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis 3(6): 578-591.

- Rosen H, Nadkarni V, Theroux M, R Padman, Klein J (1998) Intrapleural streptokinase as adjunctive treatment for persistent empyema in pediatric patients. Chest 103(4): 1190-1193.

- Krishnan S, Amin N, Dozor AJ, Stringel G (1997) Urokinase in the management of complicated parapneumonic effusions in children. Chest 112(6): 1579-1583.

- Stovroff M, Teague G, Heiss KF, Parker P, Ricketts RR (1995) Thoracoscopy in the management of pediatric empyema. J Pediatr Surg 30(8): 1211-1215.

- Steinbrecher HA, Najmaldin AS (1998) Thoracoscopy for empyema in children. J Pediatr Surg 33(5): 708-710.

- Merry CM, Bufo AJ, Shah RS, Schropp KP, Lobe TE (1999) Early definitive intervention by thoracoscopy in pediatric empyema. J Pediatr Surg 34(1): 178-180.

- Kern JA, Rodgers BM (2001) Thoracoscopy in the management of empyema in children. J Pediatr Surg 28: 1128-1132.

- Foglia RP, Randolph J (1987) Current indications for decortication in the treatment of empyema in children. J Pediatr Surg 22(1): 28-33.

- Hoff SJ, Neblett WW, Heller RM, Pietsch JB, Holcomb GW (1989) Postpneumonic empyema in childhood: selecting appropriate therapy. J Pediatr Surg 24(7): 659-664.

- Cham CW, Haq SM, Rahamim J (1993) Empyema thoracis: a problem with late referral? Thorax 48: 925-927.

- Carey JA, Hamilton JRL, Spencer DA, Gould K, Hasan A (1998) Empyema thoracis: a role for open thoracotomy and decortication. Arch Dis Child 79: 510-513.

- Hamm H, Light RW (1997) Parapneumonic effusion and empyema. Eur Respir J 10(5): 1150-1156.

- Raffensperger JG, Luck SR, Shkolnik A, Ricketts RR (1982) Mini-thoracotomy and chest tube insertion for children with empyema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 84(4): 497-504.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...